Part I: From Broken Promises to New Leverage

Why Federal Economic Policy Feels Foreign — and Why That’s Beginning to Change

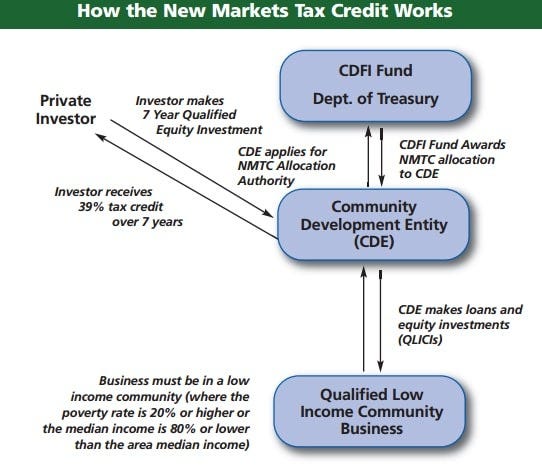

For many people, the gap in understanding around modern federal economic tools — Opportunity Zones, New Markets Tax Credits (NMTC), Historic Tax Credits, CDFIs, and CDEs — is often framed as a problem of awareness or education.

That framing misses the point.

What we are actually witnessing is the aftershock of a deliberate rupture in Black economic continuity — one that began when land redistribution was abandoned after the Civil War. The effects of that moment did not disappear. They compounded, adapted, and reappeared in new forms across generations.

To understand where we are — and where we can go — we have to connect the dots cleanly.

Economic literacy follows ownership — not freedom

After emancipation, Black people were legally free but economically disinherited. Freedom came without assets, leverage, or institutional proximity.

When 40 acres and a mule was reversed, Black families didn’t just lose land. They lost leverage. They lost the ability to transfer assets across generations. They lost daily exposure to the systems that shape policy, markets, and capital.

In the United States, economic literacy is not primarily learned in textbooks. It is learned through ownership. Farmers understand land policy because they own land. Developers understand tax credits because they build projects. Business owners learn depreciation, leverage, and capital stacks because they are responsible for them.

When Black people were systematically denied ownership, they were also denied the environment where economic policy knowledge is learned, shared, and normalized. This was not ignorance. It was engineered distance.

Federal policy became something done to Black communities, not with them

From Reconstruction forward, most federal economic interventions in Black communities arrived as relief, aid, and social services. They came with heavy compliance requirements, layers of intermediaries, and limited pathways to ownership.

Rarely did they arrive as wealth-building instruments or investor-side incentives.

Over time, a rational understanding formed: federal policy was something that managed Black communities, not something Black communities controlled. Even when programs were well-intentioned, the structure reinforced dependency rather than leverage.

Opportunity Zones and NMTCs disrupt that pattern in theory. But theory alone cannot erase generations of distrust, exclusion, and structural distance.

These tools were designed for people who already speak “capital”

Opportunity Zones and NMTCs are not intuitive. They assume fluency in tax liability, equity versus debt, timing windows, compliance structures, and investor psychology.

They were designed for developers, banks, funds, accountants, and lawyers — not for communities historically blocked from accumulating taxable income, investment portfolios, or balance sheets.

So when these tools enter Black communities, they often feel foreign. The language feels technical. The process feels opaque. And too often, the value created does not remain local.

This is not a failure of capacity. It is the predictable outcome of long-term exclusion from capital ecosystems.

Gatekeeping replaced exclusion — but the outcome stayed the same

Post–Civil Rights America rarely says, “You can’t participate.” Instead, it says, “You need sophistication,” “You need a track record,” or “You need an experienced partner.”

In practice, this often means outside developers, outside funds, and outside control. Projects happen in Black neighborhoods. Value flows outward. Knowledge stays centralized elsewhere.

This isn’t accidental. It is a refined continuation of the same logic that ended land redistribution: allow presence, but restrict leverage.

Why this still shows up as a “knowledge gap”

When people ask why more Black leaders don’t deeply engage Opportunity Zones or NMTCs, the more honest question is why Black communities were systematically excluded from the environments where this knowledge circulates naturally.

You don’t learn tax credit finance at the dinner table if your grandparents were sharecroppers, your parents were redlined, your institutions were undercapitalized, and your leadership was forced into survival mode rather than long-term positioning.

What appears as confusion is often historical memory without infrastructure.

A second chance — but not an automatic one

Opportunity Zones and NMTCs are not perfect. They can be misused, and they often are. Still, they represent some of the few remaining federal tools that meaningfully intersect ownership, capital, and place.

The opportunity now is different from the past — but only if it is claimed intentionally.

If Black communities do not build internal fluency, control deal structures, train their own developers, and own pieces of the capital stack, history does not repeat violently. It repeats politely.

The throughline we rarely name

The abandonment of 40 acres and a mule taught America a lesson: never let Black people control the base asset.

Modern policy refined that lesson: allow Black communities to host projects — but not own the leverage.

That is why education without ownership feels hollow. Representation without control feels performative. Inclusion without equity feels extractive.

Where this series is going

This first article is not about nostalgia or grievance. It is about clarity.

The issue is not that Black people don’t understand federal economic policy. The issue is that the chain that would have made that understanding organic, inherited, and normal was broken — intentionally.

Part II will explore what it looks like to rebuild that chain: how Opportunity Zones, NMTCs, and related tools function as modern land analogs — and how Black communities can move from participation to positioning.

This is not about catching up.

It is about reclaiming a lineage — and deciding, collectively, what we do with the leverage that still exists.